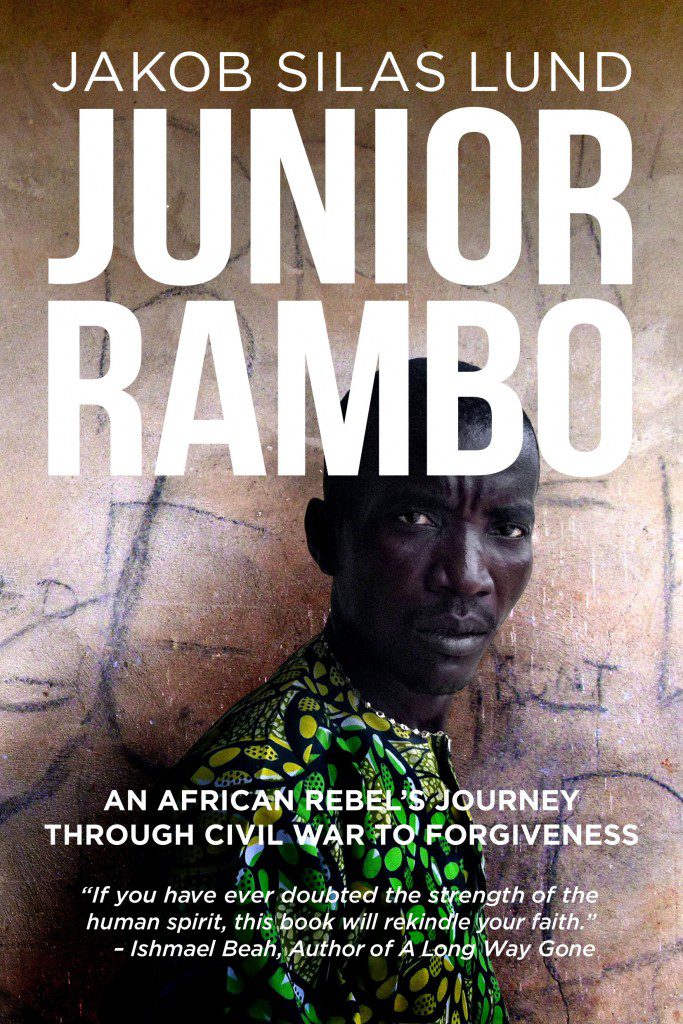

by Jakob Silas Lund

by Jakob Silas Lund

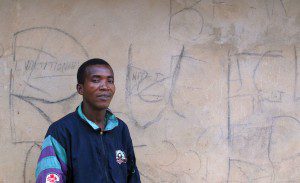

When I first met Samba, he struck me most of all as a person almost obsessively engaged in the local reconciliation process in the wake of the Sierra Leonean civil war. He was the most eager of all the participants at the first consultation among former fighters, victims and witnesses of the war, which I assisted in carrying out, volunteering with the Sierra Leonean organization Fambul Tok. This was the very last days of 2007. The consultation was to be the start of a long, fascinating reconciliation process in the area where Samba lived, and the aim was to get a sense of whether the communities were ready to start this complicated and oftentimes painful process, and what they would want it to entail. Samba later told me that he was at first reluctant to partake in the process because he feared it might be connected to a judicial process that could land him behind bars.

He wasn’t wrong to fear prosecution; Samba committed crimes during the war that would frame him as a vile criminal in the eyes of most people. But that’s exactly why—after he was assured there would be no punitive measures involved in the process facilitated by Fambul Tok—he was so persistent in his participation. He harbored a genuine and very strongfelt desire to make amends, apologize to the victims of his crimes and gain forgiveness in return.

Half a year later, I met Samba again. Now even more heavily involved in the reconciliation efforts in his community, he was part of organizing a bonfire ceremony during which victims and perpetrators were given the chance to share their experiences from the war. The event is described in detail in the book Junior Rambo, but suffice it to say here that this evening changed my life. I witnessed Samba come forth in front of a few hundred gathered villagers to confess to his wrongdoings during the war. In fact, he admitted to having killed a young boy, and he did so directly to the boy’s surviving sister. It was perhaps the most emotionally charged moment I’ve experienced in my life. Samba fell to the ground and begged the woman for forgiveness. When I added this to the volumes of knowledge Samba had shared with me about the Sierra Leonean civil war and his own involvement in it—his rise from foot soldier to bodyguard for the infamous rebel leader Foday Sankoh—I knew instantly that Samba’s story was bigger than him. And that it had to be told.

Half a year later, I met Samba again. Now even more heavily involved in the reconciliation efforts in his community, he was part of organizing a bonfire ceremony during which victims and perpetrators were given the chance to share their experiences from the war. The event is described in detail in the book Junior Rambo, but suffice it to say here that this evening changed my life. I witnessed Samba come forth in front of a few hundred gathered villagers to confess to his wrongdoings during the war. In fact, he admitted to having killed a young boy, and he did so directly to the boy’s surviving sister. It was perhaps the most emotionally charged moment I’ve experienced in my life. Samba fell to the ground and begged the woman for forgiveness. When I added this to the volumes of knowledge Samba had shared with me about the Sierra Leonean civil war and his own involvement in it—his rise from foot soldier to bodyguard for the infamous rebel leader Foday Sankoh—I knew instantly that Samba’s story was bigger than him. And that it had to be told.

Samba had gone from being a regular young man in Sierra Leone’s rural east, looking for a job and for meaning with his life, to being a hardened fighter in one of Africa’s most notorious rebel movements, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). He had killed, nearly been killed himself several times, and—because of his unique role so close to the leadership of the rebels—had knowledge about the inner workings of the war rooms. And aside from all that, he had an intriguing way of intersecting harrowing and moving details of the war with anecdotes about pet monkeys and common jealousy.

Samba had gone from being a regular young man in Sierra Leone’s rural east, looking for a job and for meaning with his life, to being a hardened fighter in one of Africa’s most notorious rebel movements, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). He had killed, nearly been killed himself several times, and—because of his unique role so close to the leadership of the rebels—had knowledge about the inner workings of the war rooms. And aside from all that, he had an intriguing way of intersecting harrowing and moving details of the war with anecdotes about pet monkeys and common jealousy.

When Samba and I said our goodbyes the day after the bonfire ceremony, I told him that someone needed to write his story. My mind was blown away by the capacity and desire for reconciliation I had witnessed; by the unique insights into how a war machine works; and by Samba’s account of how life continues in the face and aftermath of war. And I was sure these stories would equally move other people with a similarly meager direct experience of war. I was sure Samba’s life story could serve to teach people outside of West Africa and outside the immediate danger of war a great deal about humanity and about what human beings are capable of. Nothing less.

When I reconnected with Samba a few years later through Play31, his life hadn’t been turned into a page-turner. So I decided to embark on that process myself. I interviewed Samba, his family, friends and former enemies and a range of experts, including anthropologist Paul Richards, local military experts and former US Ambassador John Hirsch. The result is Junior Rambo.

When I reconnected with Samba a few years later through Play31, his life hadn’t been turned into a page-turner. So I decided to embark on that process myself. I interviewed Samba, his family, friends and former enemies and a range of experts, including anthropologist Paul Richards, local military experts and former US Ambassador John Hirsch. The result is Junior Rambo.

I’m happy with how it turned out, and so is Samba. Every time we speak—whenever Samba is able to get a network connection for his old phone—he asks me whether new people have read about his story. He is ecstatic whenever I tell him that this group of school children or that individual with no prior knowledge of the Sierra Leonean civil war enjoyed the book. It makes me happy, too, and I hope Junior Rambo can contribute to a greater understanding of what it means to live through war and about how people can come out on the other side.

Jakob S. Lund is the author of Junior Rambo, as well as the founder of Play31, an organization that uses football to bring together communities torn apart by the war in Sierra Leone, and trains women, men and children in human rights and conflict resolution. Jakob currently works for UN Women in Bolivia where he focuses on violence against women.