In Part 2 of 2, guest contributor Vasilis Migkos interviews the co-founder of Peace Action Training and Research Institute of Romania (PATRIR) and the director of its Department of Peace Operations (DPO), Kai Brand-Jacobsen who shares his experiences, emotions, thoughts and ideas about peacebuilding in Cyprus. (Read Part 1.)

In Part 2 of 2, guest contributor Vasilis Migkos interviews the co-founder of Peace Action Training and Research Institute of Romania (PATRIR) and the director of its Department of Peace Operations (DPO), Kai Brand-Jacobsen who shares his experiences, emotions, thoughts and ideas about peacebuilding in Cyprus. (Read Part 1.)

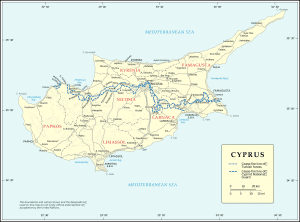

Kai, as far as I know, one of your peace operations took place in Cyprus. Yes. We work to support initiatives and actions – what’s being done for peacebuilding – by people within their countries and their communities. In this case, I was asked by organisations in Cyprus to come and speak at an event which brought together both Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot organizations. I spoke on the links between peacebuilding and development with an international focus but was also asked to share experiences from peace processes and peacebuilding experiences from different areas around the world that we have been involved in. The audience was made up of a large number of different types of organizations including civil society organizations, chambers of commerce, journalists, representatives of unions, academics and political leadership advisors. It included the first day’s presentation and interactive discussions and then I was asked to meet with journalists and some individuals from both sides and gave a presentation in the evening to a broader range of the community including diplomats, academics and others, focusing on the role of media, the influence that media on both sides can have on the conflict. The second day, some of the people that were involved in mediation and peace initiatives during the last 10, 20, and even 30 years, people from the island and others, were gathered to work on a tool we call a peace profile. It was to try to map what was done, by whom, up ‘till then, to try to deal with the conflict issues.

So, it’s obvious that your strategy had to do with bringing all these institutions and organizations together for a sincere and productive dialogue and at the same time mapping what had been done in order to gain from this experience and move on with the other peacebuilding initiatives. Having what we call a multi-stakeholder approach is very beneficial. The two subsequent events that came out of this were multi-stakeholder strategic planning processes. They were held in different locations in the island and a number of individuals from across the spectrum of society were involved—such as people that were working with business and economic interests, key journalists, authors and writers, teachers, people that were deeply involved in civil society and the NGO sector, people that were advisors in different political parties. Also, colleagues from both communities that have been involved in cross-community dialogue bringing people together came and showed a short film clip that lasted a few minutes. It was a “news story” from the future, showing the island united, to add to the motivation and the commitment that people felt. That event was followed up a few months later by another event “Building the Future of Cyprus” which was not just dialogue – it was also very clearly action-oriented. This is critical. People often get frustrated by processes where they just come together and speak. It helps practically work to find ways to commonly address the future and the issues that are important to people, and also give space to hear people’s experiences of the past, respecting them, hearing each other authentically and building together from there to move forward. This creates and generates a greater engagement.

What were the outcomes and the impact of that action? There were three different events in total. The first one was two days and included a talk. The second one was three days together, much more in depth. The third one was the “Building the Future of Cyprus: Bridging the Divide” three-days multi-stakeholder strategic planning process. There we brought together many of the same participants as well as a few others and we really moved towards what they feel are the key areas of work needed to bring meaningful change in the situation. It led to some concrete cooperation projects; it has led to improving skills and people have found ways to engage. Sustained activity and concrete initiatives that carried the work forward were important. These three events were aimed at bringing people together and helping to train them with deeper skills in peacebuilding and working with conflict, learning from experiences on the island, critically and practically reviewing them, drawing lessons, and learning also from the state of the art of the field and practical experiences on the ground from other contexts. If we really want to see the impact, we have to look at what has been followed up on – what has been done further by those who participated. There are some extraordinary individuals that were involved in a number of initiatives that make connections between people’s skills and ideas across the island.

What were the outcomes and the impact of that action? There were three different events in total. The first one was two days and included a talk. The second one was three days together, much more in depth. The third one was the “Building the Future of Cyprus: Bridging the Divide” three-days multi-stakeholder strategic planning process. There we brought together many of the same participants as well as a few others and we really moved towards what they feel are the key areas of work needed to bring meaningful change in the situation. It led to some concrete cooperation projects; it has led to improving skills and people have found ways to engage. Sustained activity and concrete initiatives that carried the work forward were important. These three events were aimed at bringing people together and helping to train them with deeper skills in peacebuilding and working with conflict, learning from experiences on the island, critically and practically reviewing them, drawing lessons, and learning also from the state of the art of the field and practical experiences on the ground from other contexts. If we really want to see the impact, we have to look at what has been followed up on – what has been done further by those who participated. There are some extraordinary individuals that were involved in a number of initiatives that make connections between people’s skills and ideas across the island.

What did that process teach you? It highlighted once again that there are great initiatives that have been done and people who are passionate and dedicated to working for change. There have been people who suffered or had negative experiences from the war and the division and want to address it. There are people who believe in and want to see something better for themselves and the island and constantly undertake activities to make that happen. That is powerful and inspiring… but it is not enough. We also need to see what is fueling the conflict and not just falling into the easy stereotype of blaming one side or the other, saying “It’s all their fault.” What are the policies, the structures, the issues that need to be addressed? What are the underlying causes? We need to broaden the engagement of other key sectors. This process also highlighted the importance of hope. There are so many people working on conflicts who do not necessarily believe that they will succeed. There have been other conflicts where many more people suffered and lost their lives and that were resolved. There is the intelligence, the ability and the desire among so many all over the island to find something better and it can be done.

So all we need is just to organize? Organising is important and it’s a key part of it, but it’s not enough. We need to involve much larger segments of the society and not just leave it in the hands of those who have not yet been able to create peace. We need to really, seriously learn from past experiences, and bring together the extraordinary intelligence, creativity and desire for something better that is – in reality – felt by many people on all sides of the island. We need to have the courage to go beyond just accepting the normal ‘patterns’ of the conflict, and to challenge and transcend them. It is not enough to focus on diagnosis and analysis of the problems. We also need to come up with visible and practical solutions – and then work so that the overwhelming majority of people on all sides of the conflict see the concrete value of those solutions, and mobilise to make them happen.

There have been many long discussions about the Kofi Annan Plan. Why do you think it was rejected? In your opinion was it a good plan? From what many people I’ve met, discussed with and listened to on Cyprus have said, there were definitely elements of the plan that addressed issues important to them, issues at the heart of the conflict, and offered practical and in some ways attractive solutions. Some of its implementation aspects, though, could have been improved. It could have been linked more directly with the entry of Cyprus into the EU, creating greater incentive that would have helped in the unification of the island and then entry into the EU. Although they tried to bring together the key actors, there are some – including in the EU – who have suggested that not enough attention was paid to those sectors and institutions which did not support the process and actually carried out active campaigns against the Annan plan.

There have been many long discussions about the Kofi Annan Plan. Why do you think it was rejected? In your opinion was it a good plan? From what many people I’ve met, discussed with and listened to on Cyprus have said, there were definitely elements of the plan that addressed issues important to them, issues at the heart of the conflict, and offered practical and in some ways attractive solutions. Some of its implementation aspects, though, could have been improved. It could have been linked more directly with the entry of Cyprus into the EU, creating greater incentive that would have helped in the unification of the island and then entry into the EU. Although they tried to bring together the key actors, there are some – including in the EU – who have suggested that not enough attention was paid to those sectors and institutions which did not support the process and actually carried out active campaigns against the Annan plan.

When it comes to Cyprus, what were the sectors that were excluded? From what I understand the Greek Cypriot Orthodox Church became a strong opponent to the process in many ways. There were issues such as how to handle lands that were in the Turkish Cypriot part of the island and various concerns that they had. The Church’s opposition had a strong influence on many. More could have been done, during the negotiation process and the later campaign, to identify obvious risks and challenges, and potential negative scenarios, to take them more seriously, and to see how to engage those actors who became opposed to the initiative. The challenge afterwards was that many people who had campaigned hard and placed their hopes in a resolution of the conflict felt very defeated. The result itself could easily have been foreseen by using the tool of scenario planning. You are doing a campaign. What are the different scenarios? What might go one way or another? And what do we need to do to try to make sure that the more positive and constructive outcome we are trying to achieve is realized? It’s amazing to realise but most high level negotiations and peace processes do not use such a basic tool which could help in identifying ahead of time risks / challenges and seeing how to build practical strategies into the process which could overcome or prevent them.

How do you see the role of Greece and Turkey on the island? Is it positive? Is it negative? If it is negative could it be positive? Should Cyprus deal with this by itself? I think there are elements of both. Clearly, both populations do feel connections with their allied countries, Greek Cypriots with Greece and Turkish Cypriots with Turkey. Both countries have a long history of involvement on the island—cultural, historical, political, economic etc. But it’s the people of the island that have to find the solution. Using the other, Greece or Turkey, as an excuse to say, “Oh what they are doing makes it impossible” is not effective. If the people of the island authentically visit, engage, recognize and treat each other with legitimacy and respect, then there can be solutions. There are very clear reasons both for Greece and for Turkey why they would benefit from supporting this and we must make it visible. I would also suggest that more needs to be done by media, academicians, think tanks, and NGOs to create multiple channels of cooperation and look both at the Turkey-Greece and the Turkey-Greece-Cyprus relationships.

There is an ongoing discussion on how the experience gained from the peace process in Northern Ireland can contribute to the solution of Cyprus issue. There are probably a few thousand lessons that could be learned from Northern Ireland. Cyprus has its own experiences. It is important to look within our own context so we can learn about what has happened. At the same time, there are some interesting lessons and parallels from the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 between Dublin and London, that could be relevant for the Turkey-Greece dimension. The robust and significant engagement of civil society of Northern Ireland – including combatants and prisoners who played key roles in mobilization to bridge the divide and stop the violence – could also be interesting in the context of Cyprus. Many citizens, in both cases, became tired of the situation, saying, “We need something better.” The economic downturn is also affecting both Northern Ireland and Cyprus and has begun to make the potential benefits of the reunification clear.

As a Greek, I feel I have hopes. A friend of mine once said: “I am neither an optimist nor a pessimist, but I have hope born of the choices I make and the action I take.”